- Michael Drayton, Poly-Olbion, 1612. Collection Flash of Splendour.

“Michael Drayton…produced (the) perfect Golden work, so pure and fine that no English poet has rivalled it. Gold ‘to ayery thinnesse beate, without weight, ready to leave the earth.”

C. S. Lewis

Anyone who has read a long poem day after day…knows how the poem comes to possess the reader and how it naturalizes him in its own imagination and liberates him there.

Wallace Stevens

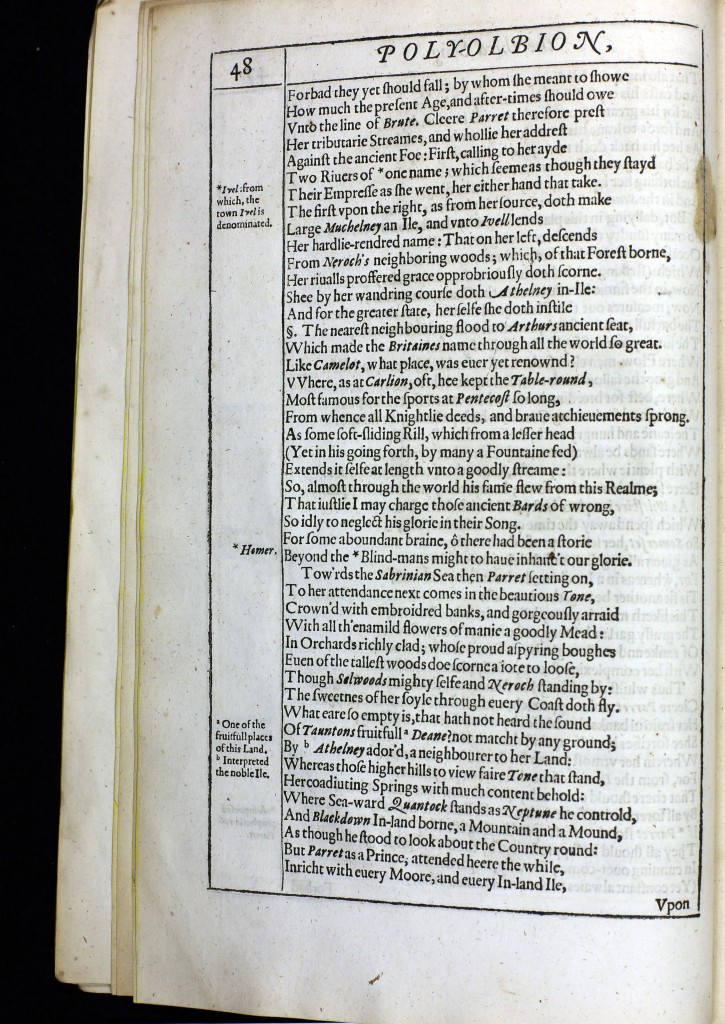

After twenty years of writing and research, in 1612, Michael Drayton published the first part of his magnus opus, Poly-Olbion, a vast and hugely ambitious poem celebrating the countryside, history and antiquities of England and Wales. He eventually managed to get the second section to print in 1622, following a series of increasingly vitriolic exchanges with publishers who were wary after slow sales of the first volume: “It went not so fast away in the Sale, as some of their beastly and abominable trash,” he grumbles in the preface, “the Booksellers and I are in Terms: They are a Company of base Knaves, whom I both scorn and kick at.”

Drayton describes Poly- Olbion’s long, troubled gestation as his “strange Herculean toyle” and the creation of this extraordinary poem, one of the longest of its kind in the English language, with its almost 15000 lines of Alexandrine verse, seems to have driven him almost to madness, certainly to utter despair at points in its birthing. As Thomas Campbell wrote in his British Poets of 1819, he “treated the subject with (such) topographical and minute detail as to chain his poetry to the map.”

Drayton’s over-work and anguish nevertheless resulted in one of the most important texts in English literary history. In his 1612 dedication to Henry, Prince of Wales, he writes that his poem is “first in this kinde” and, whilst models for the concept and content can be found (he drew heavily on his friend William Camden’s 1586 Britannia, for example), the sheer breadth of the Poly-Olbion project has never been equalled, not least as a vast repository of early seventeenth life and thought.

The structure is simple: a unnamed muse (the “Genius of the Place”) leads the poet on her “progresse” through the country (echoing Elizabeth I’s royal tours), providing a county-by-county description, each in the form of a separate Song, of all the “Tracts, Rivers, Mountaines, Forests, and other Parts of This Renowned Isle of Great Britaine, with Intermixture of the Most Remarquable Stories, Antiquities, Wonders, Rarityes, Pleasures, and Commodities of the same.” The first part consists of eighteen Songs, each one prefaced by a fantastical engraved map by William Hole (see pages 22-31) and followed by a learned prose commentary by the antiquarian John Selden; the second volume offers twelve songs, again with engravings, but no exegesis.

Poly-Olbion emerged from the late 16th and early 17th century vogue for chorography: the description or de-lineation of regions or districts, as opposed to geography, which studies the “whole known world…together with the phenomena which are contained therein,” according to Ptolemy’s standard definition or locus classicus in his Cosmographia. Chorography deals even “with the smallest details, such as harbours, villages, districts, tributaries, and such like….Its concern is to paint a true likeness, and not merely give exact position and size….Chorography needs an artist, and no one presents it rightly unless he is an artist.”

According to Ptolemy then, rather than a dry survey or verse chronicle, Drayton’s daring poetic structure, closely illustrated by Hole’s allegorical cartography, was the perfect vehicle for the most extensive chorographical description yet attempted of Great Britain. One of the most striking features of the Poly-Olbion is Drayton’s use of prosopopoeia, the personification of landscape – rivers, hills, islands, ditches, moors – to convey historical, legendary, topographical and allegorical information. Virtually every natural feature that the poem includes is described as a human or mythical entity, a characteristic which is closely reflected in the iconography of the Hole maps which accompany each Song. Many of the features converse or interact with each other through contests or romantic liaisons: Watling Street asks the River Ver to explain the changes time has brought to the St Albans area; the Gogmagog Hill comically woos the River Granta, and the Isis marries the Tame to produce the River Thames.

While this chorographical journeying around England and Wales focuses on the detail (Poly-Olbion is full of rich encyclopaedic lists, for example, vital to modern historians, such as a long catalogue of names of English birds in Songs XIII and XXV), Drayton’s wider aim for his opus was sweeping: to portray, through the juxtaposition of these multiple disparate parts, narratives and anthropo-morphised landscape features, a unified, heroic image of a great vibrant Britain, where the very hills are alive with story and song. In this way, the poem transcends and fulfils its oxymoric title: Poly-Olbion, the manifold or multiple Albion (the ancient name for Britain), where the local and national, the excluded and included, are united and come together as one.