Upon the Frontispice

Through a Triumphant Arch, see Albion plas’t,

In Happy site, in Neptunes armes embras’t,

In Power and Plenty, on hir Cleeuy Throne

Circled with Natures Ghirlands, being alone

Stil’d th’Oceans*Island. On the Columnes beene

(As Trophies raiz’d) what Princes Time hath seene

Ambitious of her. In hir yonger years,

Vast Earth-bred Giants woo’d her: but, who bears

In Golden field the Lion passant red,

Aeneas Nephew (Brute) them conquered.

Next, Laure at Caesar, as a Philtre, brings,

On’s shield, his Grandame Venus: Him hir Kings

Withstood. At length, the Roman, by long sute,

Gain’d her (most Part) from th’ancient race of Brute.

Divors’t from Him, the Saxon sable Horse,

Borne by sterne Hengist, wins her: but, through force

Garding the Norman Leopards bath’d in Gules,

She chang’d hir Love to Him, whose Line yet rules.

Cleevy: abounding in cleves or cliffs

Passant: a heraldic four-legged animal, walking and looking ahead.

Gules: red, one of the main heraldic colours.

Thoughts on the Frontispiece

The Poly-Olbion title page, the defining image of the poem, addresses the unificatory relationship

between land and nationhood that marks Drayton’s chorographical project. Albion, depicted as a beautiful woman wielding the symbols of “Power and Plenty,” the sceptre and cornucopia, is robed in a map of England, woven with the very geography that crowds the pages of the poem, her physical shape resembling the “Isle of Wonders” that she represents. The male figures framing her are identified by Drayton in his accompanying lines Upon the Frontipiece: Albion first being conquered by the Trojan Brute, then initially repelling the love philtres proffered by Julius Caesar, but eventually relenting to his long suit. Their subsequent divorce enables the Saxon raider Hengist (bottom left) to overcome her. However, she swiftly “chang’d hir Love” to the Norman conqueror, William (lower right), whose “line yet rules.”

Comparison with another work in the exhibition, the 1610 Frontispiece from William Camden’s

Britannia, also by William Hole, shows a shift in perception of sovereignty and the land. In Camden, the page is dominated by the map, with the allegorical figure of Britannia present, but placed in a separate marginal vignette; in Drayton, the figure of Albion is gigantic and inseparable from the eternal landscape, the mortal monarchs, representative of the Isle’s four bloodlines, are cast as shifting and intransient, literally in the margins. Her throne is similar to that seating Elizabeth in the earlier Saxton Frontispiece, which was in turn a reuse of iconography of the Virgin Mary as Queen of Heaven. The cult of Mary is thus replaced by Elizabeth and, now, with Drayton and Camden’s vast chorographical projects, the cult of Britain, of the land, assumes ascendancy in turn.

Anne Louise Avery, Flash of Splendour

One of the most striking royal images of the Elizabethan era, the Ditchley Portrait (below left), portrays the queen standing on a huge map of Britain. This picture was painted around 1592, just over a decade after Christopher Saxton produced the first atlas of England and Wales. As a result, Elizabeth’s subjects were conceiving of their nation in new ways.

William Hole’s engraved frontispiece for Poly-Olbion, produced two decades later than the Ditchley Portrait, takes established cartographic imagery and moulds it into new forms. For Hole, the central figure is Albion, an anthropomorphized realization of England. Albion is wildly regal. Positioned centrally under a triumphal arch, with ships in the background suggesting military and economic might, she projects serene authority. Yet her bare feet and breast, and her untamed tresses, bespeak nature rather than culture, and this is underscored by the cherubs hovering at her head, holding (in the words of the accompanying poem) ‘Natures Ghirlands’. In one hand Albion holds a cornucopia: a goat’s horn overflowing with fruit and grain. In the other hand she grips a sceptre, the symbol of royal authority preferred in portraiture by the two Tudor queens, Mary and Elizabeth.

It is easy enough to interpret Albion as the land figured in feminine form, exposed to the gaze of the civilizations that will in turn take and reshape her. These forces are represented in Hole’s image by their armed male leaders: the Trojan Brute, Julius Caesar, the Saxon Hengist, and William the Conqueror. But Albion is more than a prize. Her body suggests an integrity and fertility that are inscrutably impervious to the successive waves of conquerors. Her robes, meanwhile, are central to the engraving, figuring the contours of the landscape as inherent to the nation’s identity. Rivers and hills thus suggest at once the natural structures of the land and the mysterious inner workings of a body. Interestingly, there are also a large number of buildings and settlements marked on her gown, especially when compared with Poly-Olbion’s county maps. The walled town (possibly London), nestled in Albion’s womb and shielded by her forearms, is of her own making. Place, as much as the conquering forces, is posited as a determinant of human culture.

But what, finally, is this place? While the poem identifies the figure as Albion, her feet rest on the words ‘GREAT BRITAINE’. A model of insular nationhood was fostered by cartography; the nation was, in the words of Richard II’s John of Gaunt, a ‘sceptered isle’. But the dream of a united British island remained not only controversial, but closely identified with King James VI and I. Since Drayton had despaired of his new king within just a few years of his succession to the English crown in 1603, and famously omits him from Poly-Olbion’s catalogue of monarchs, he was unlikely to allow a piece of Jacobean propaganda on his poem’s title-page. Nationhood was instead – as it remains to this day – a rather more a fraught matter for Albion’s inhabitants.

Professor Andrew McRae, University of Exeter

In William Hole’s frontispiece to Drayton’s Poly-Olbion, the magnificent queen or goddess Albion is girdled by the figures of four male conquerors, situated in the four corners. In the upper left corner stands Brutus, the legendary descendant of the Trojan Aeneas, who was supposed to have settled Britain in the twelfth century BC. Facing him with a haughty frown is Julius Caesar – also, according to legend, a descendant of Aeneas – whose attempted conquest of Britain in the first century BCE marked the beginning of Roman dominance. In the lower left we find Hengist, the legendary leader of the Germanic bands who conquered and settled much of southern Britain at the dawn of the middle ages. The lower right is occupied by William the Conqueror, whose Norman army defeated the English under Harold Godwinson at Hastings in 1066.

In comparison to the dominant, regal figure of Albion herself, these four warlords appear both puny and marginal. They may gaze on her with ambitious eyes, or confront their rivals with jealous frowns, but none of them is really a match for the goddess they all seek to conquer and possess. The essence of “Great Britaine,” Hole’s image argues, lies in the land itself, not in transitory dynasties and modes of government. The verses accompanying the frontispiece conclude with the statement that William the Conqueror’s “line yet rules” – even as the poem appears to celebrate the union of the Norman-descended dynasty and the British land, it reveals their marriage as temporary. In due course another political order will no doubt displace William’s line, whilst Albion will remain her serene, endlessly plentiful self.

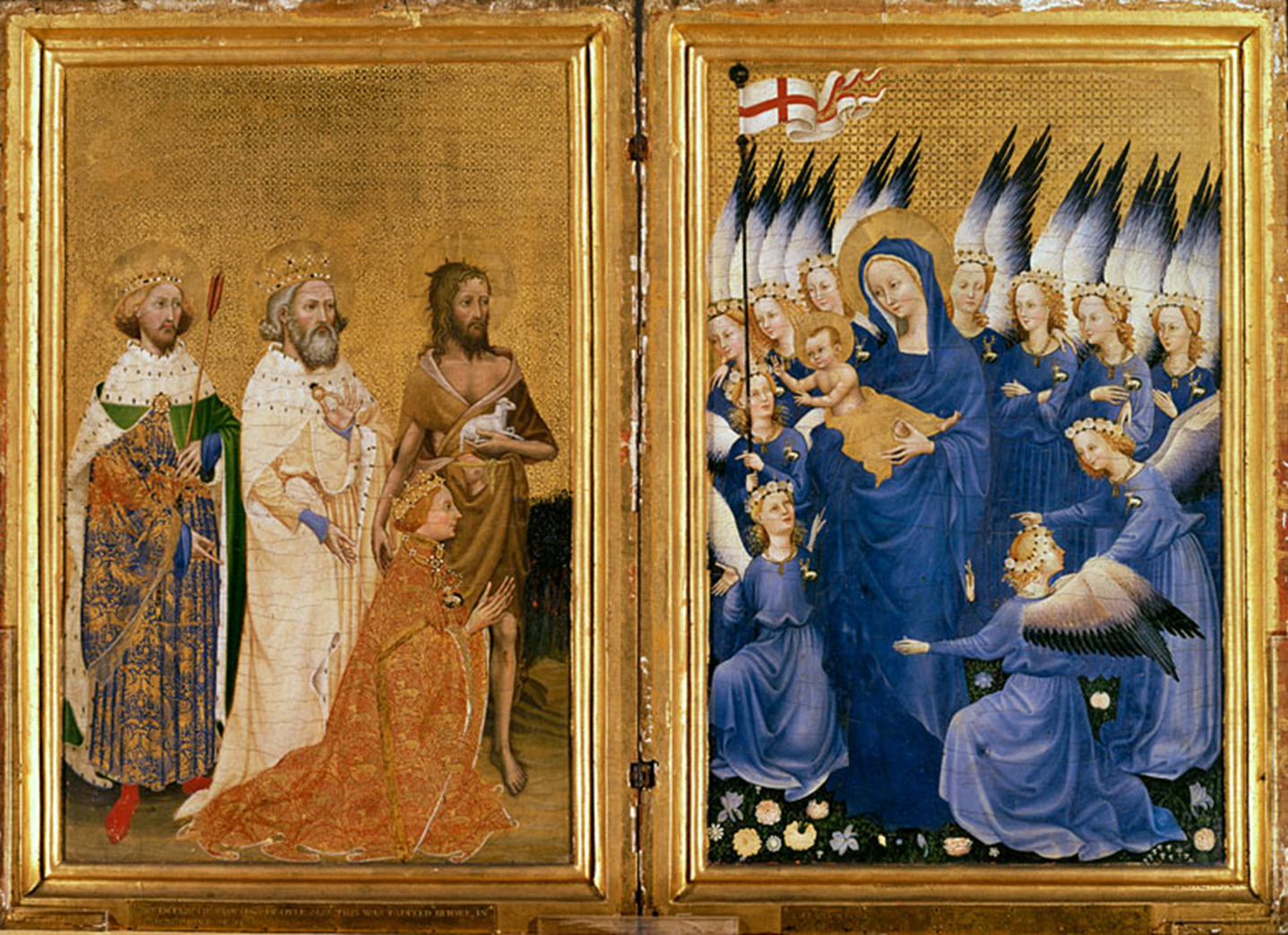

The frontispiece presents an image of the relationship between the eternal land and its transitory rulers that would have been difficult to conceive of in earlier centuries. The contrast with a late-medieval image such as the well-known Wilton Diptych is clear and illuminating. In the diptych, King Richard II occupies the foreground, and is depicted on the same scale as the host of holy figures whom he worships; the land of England is not absent from the tableaux, but it is confined to a small orb at the upper edge of the diptych. In the Wilton Diptych, the King is all and all, whilst the land is essentially a bauble. In the Poly-Olbion frontispiece, those positions have been reversed.

Whilst the four masculine conquerors are all marginal in relation to the feminine spirit of the land, this is not to say that there is no difference or distinction between them. Both the frontispiece and the accompanying poem place much emphasis on heraldry, displaying and explaining the coats of arms of the four conquerors. If we venture to read the frontispiece itself in heraldic terms, it is noteworthy that Brutus the Trojan, in his simple tunic, occupies the upper left quarter, the position of greatest honour. By contrast, the gorgeously crowned and armoured William the Norman is consigned to the subordinate lower right. From this inferior vantage-point he peers jealously upward at the beautiful Albion (though his eyes seem fixed on her sceptre rather than her face). The frontispiece thus seems to exalt the simplicity and honest valour of the ancient Britons, as opposed to the pretensions of latter-day rulers such as James I.

Professor Philip Schwyzer, University of Exeter