John Garth, A Flash of Inspiration

From Oxford Today, 12 February 2015 (online and printed)

http://www.oxfordtoday.ox.ac.uk/culture/videos-podcasts-galleries/flash-inspiration

How do you get children with special educational needs to engage with learning? Keep it simple, yes? See how one Oxford charity is doing just the opposite — using ‘high art’ to inspire and to change lives.

An Oxford-based charity founded in memory of a St Anne’s College alumna is changing the rules on how to reach out to marginalised children and young adults. Flash of Splendour works to empower them through the creative arts. Using an innovative immersive approach, it specialises in enabling access to history, art and texts that are typically considered too dry and too difficult for children with special educational needs to understand, interpret or enjoy. The aim is gloriously to uproot entrenched ideas and preconceptions about the potential of children on the margins — what they can achieve, experience, imagine and create.

Each of their projects typically ends with an exhibition, publication or film: putting the children’s voices and work into public, often highly visible arenas, such as museums.

Felicity Anne Avery, inspiration for Flash of Splendour

Founded in 2009 in memory of Felicity Anne Avery (above), Flash of Splendour’s first project enabled a group of talented teenagers with autism, and learning disabilities to exhibit a selection of paintings at St Anne’s, to profound and life changing acclaim. Two of the artists’ works were acquired by Downing Street; another, a portrait of St Anne, is now prominently displayed at the college.

Later projects have seen collaborations with schools across Britain, and partnerships with the Oxfordshire Museum, the Ashmolean Museum, the English Folk Dance and Song Society at Cecil Sharp House, Barefoot Books in Oxford, cartographic artist Stephen Walter, Blackwell’s, Wytham Woods and local literacy charity Bookfeast.

Since last year, they have been working in partnership with Exeter University and the Royal Geographical Society on their most ambitious project yet, for which they were awarded major Heritage Lottery and Arts and Humanities Research Council grants: the Children’s Poly-Olbion, which introduces children to Michael Drayton’s vast topographical poem of Britain, Poly-Olbion (1612; 1622). Their reimagining of Drayton’s Jacobean landscapes will be showcased, alongside 17th-century books and maps, at the Royal Geographical Society in London in a month-long exhibition from 9 September. The first Flash of Splendour literary festival will be also held during the show’s run on 19 and 20 September and will explore ideas of English landscape and identity, with speakers including cartographic historian Jerry Brotton and poet Paul Farley.

The name ‘Flash of Splendour’ originates in Dante’s Purgatorio: ‘Suddenly a flash of splendour rent the curtain of my sleep.’ It was also the title of a 1968 novel by Felicity Avery, née Bridgen, writing under the nom de plume Anne Stevenson. For her, it encapsulated the idea of the world being forged anew in 1848, when the novel is set; she had studied Dante under historian Marjorie Reeves at St Anne’s in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. Avery’s daughter Anne Louise Avery, a co-founder and director of Flash of Splendour, says, ‘Whilst she used the phrase to invoke the transitory radiance of the revolutionary spirit, we felt that it also encapsulated our ethos: each exhibition representing a temporary “flash of splendour” permanently transforming and illuminating lives.’

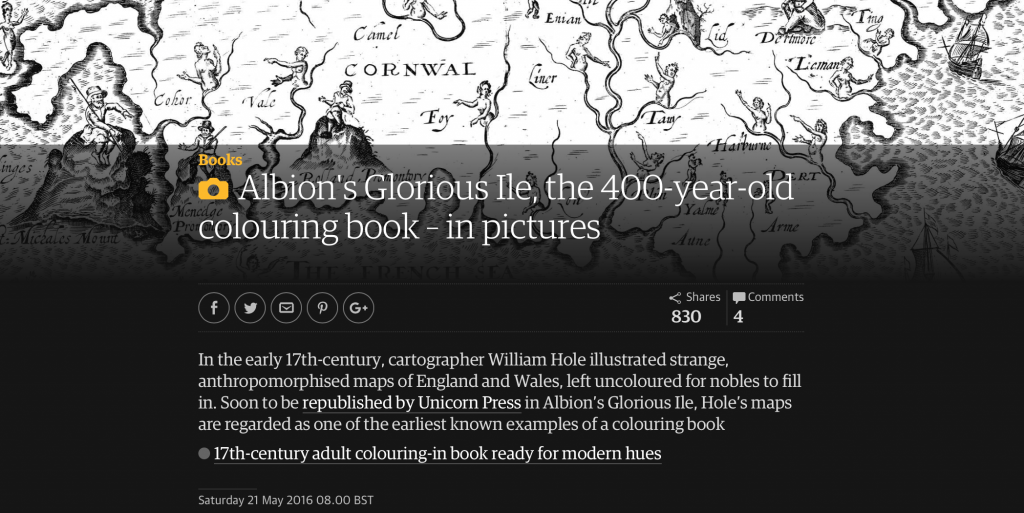

Alison, Flood, Albion’s Glorious Ile, the 400-year-old colouring book – in pictures

Alison, Flood, Albion’s Glorious Ile, the 400-year-old colouring book – in pictures

From The Guardian, 21 May 2016

In the early 17th-century, cartographer William Hole illustrated strange, anthropomorphised maps of England and Wales, left uncoloured for nobles to fill in. Soon to be republished by Unicorn Press in Albion’s Glorious Ile, Hole’s maps are regarded as one of the earliest known examples of a colouring book

Link: https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2016/may/21/albions-glorious-ile-the-400-year-old-colouring-book-in-pictures

Tim Adams, Artist Stephen Walter: ‘My maps are all about human residues and traces’

From The Observer, 9 May 2015 (online and printed)

The Londoner’s huge, highly detailed hand-drawn plans of the metropolis record long-forgotten histories and recent redevelopments with a critical eye, and echo Iain Sinclair’s psychogeography

I meet Stephen Walter outside the Aquatics Centre at the Olympic Park in east London, in order to walk back to his studio near Fish Island on the River Lea just beyond the perimeter fence. Walter is London’s compulsive cartographer. His hand-drawn map, The Island, which views the whole metropolis through a labour-of-love series of tiny pencil-noted public and private associations, all set adrift in a Kentish and home counties sea, is one of the indelible reimaginings of a city that has always lived most vividly in the minds of its artists.

The Island, about to be published in book form, is part oral history, part folklore, part personal homage, and was completed in 2008, when this park was still being cleared. Walter denoted the site as a set of Olympic rings between the football pitches of “hack ’em down” marshes and an ironic “end of the world” line that marks the border with Newham (“worst life expectancy – female”) and competing associations of “McGrath Waste Management: a terrace of clank and dust, hear the noise and feel it in your eyes”, “paint, glue and parafin[sic]” works, “African mirical [sic] believers” and “new city pads?”. If he were to redraw his Island now – and he has plans to do maybe two or three more versions in his lifetime – then it would include one or two different magnifying-glass impressions of the place he has experienced since then, which he annotates in conversation as we walk.

For a start, a revamped map might record that those “paint glue and parafin” factories had been compulsorily purchased. And that in their place had come the stadiums and the Olympic Village, sold off as the “city pads” he prophesied, the Westfield shopping centre, landed from Oz, what he calls by turns a “modernist utopia seen through a corporate prism”, “a consumption theme park for somnambulists”, “a monolith of organised fun”, and a “futurist battleground for West Ham and Millwall fans”.

Walter’s studio has been on the margin of this site throughout the transformation. He remembers when the blue fence went up around the Olympic Park and construction began. He is an inveterate urban adventurer – for his subsequent subterranean version of his Island map Walter occasionally wandered old sewers with his friend, the celebrated “place hacker” Bradley Garrett, (motto: explore everything), who, he says, treats “the whole urban landscape as if he were a curious child”. In this sense, to Walter, a cheerful trespasser, the blue fence was fighting talk. “I broke in and started walking around the Olympic construction site on a Friday afternoon,” he remembers. “There was no one around except a few bods in yellow jackets. I was just exploring the abandoned factories. Litter-strewn, stripped out, the titty calendars still on walls. I love that idea of ruin – it is food for the curious brain. Anyway, I was wandering around and this security car pulls up and an eastern European skinhead guy got out and pointed a machine gun at me.”

The full-on Olympic experience, I suggest. What happened?

“I was like ‘Easy – I just got lost.’ Fortunately he had a colleague with him, a London Rasta, who calmed him down and asked me quite politely to leave.”

We walk along the wide post-Olympic avenues, with their insistent flags still flapping three years after the event: “Discover. Share. Enjoy.” We are the only people in evidence. “It was odd here before,” Walter says. “Almost like a borderland, quite creative. It was tacky, but things were being made. Quite big factories, and a mix of small business and design studios. I don’t know whether it will ever be properly used now, it will always be becoming something. Still, there is an Apple Store at Westfield, so I can’t really complain.”

I suppose you could say that Walter works in the same tradition or space as Iain Sinclair or Peter Ackroyd, London’s psychogeographers, but what he does is both more visual and freer in spirit. His studio, when we get there, exists in that developers’ limbo between warehouse – it was part of the Percy Dalton salted peanut factory – and loft apartment. The rent is due for renegotiation in five years at which time, Walter imagines, the artists and makers will be priced out, having served their hipster purpose, and the buildings will become asset-class residential opportunities. In the meantime, the space is the perfect home for his site-specific one-man industry.

The walls are lined with fastidious works in progress in Walter’s two chosen forms – firstly, semi-abstract landscapes and wildernesses, each one intensely finely detailed, full of recurrent hand-drawn natural details, and secondly, maps and plans. He is working on the first draft of a commission from a charity called Flash of Splendour Arts, which works particularly with autistic and refugee children. The commission is to update the maps that accompanied Poly-Olbion, John Drayton’s epic poem of the counties of Britain, published in two parts in 1612 and 1622. Walter’s early outline views Britain – topically – spreading out from Edinburgh; he is using nuclear power stations as his orienting features.

On a nearby work table is a comparable project, just completed: a beautiful map of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, 500 years after it was first conceived, with all the imagined history since inked in. In Walter’s version the passage of time has not been kind to the original communalist paradise. A capitalist revolution has occurred in about 1900 and the resultant island state is now an edgy holiday destination, a “leisure island”: “There is a mass tourist part, here,” he says, talking me through it, “a sunset coast, the Costa Del University of the Third Age. This is where the proletariat still live. There are some Utope separatists. MoD lands, inevitably. A surfing spot. It has all become ghettoised, branded, a land grab, basically…”

Walter, 39, grew up in New Barnet. His father was a policeman, his mother an émigré German originally from the Black Forest region. Barnet is the northernmost suburb – or coastal town – of his original London Island. “If you went to the end of my road you could see the woods on the edge of the city,” he says of his childhood home. He has, as a result, he suggests, always subsequently gravitated inwards to the urban centre, or outwards in search of wilderness.

As a student his art was quite expansive, gestural; he was drawn to search out little utopias, haunted forests.

He had the idea that immersing himself in them might put a bit of “William Blake magic back into a society that has become very formulaic – anyway, that was the idea.”

At the end of one day at the Royal College of Art working on screen prints, he watched as the technician who had been helping him collected the excess ink that had been used and poured it into great big containers. Walter asked him what he was doing. When the technician explained that the waste ink was collected in lorries and taken to a toxic waste site, it got him thinking.

“I am a consumer of the world’s resources as much as anyone else,” he says now, “I don’t claim any virtue or anything, but on the other hand I do think trees are sacred things. It did hit me that in trying to capture that fact, one of the main things I was actually creating was this toxic waste…”

One response to that was for Walter to embark on a drawing that wasted nothing, and “literally took me two years”. It was a multilayered pencil street map, one sheet on top of the other, of places that were important to him. “The only environmental damage in that was to my hand and elbow and my time and my eyes,” he says. That was the beginning of his “slavish” current methods, building up sign and symbol over hours and weeks and months.

It is tempting, Walter suggests, as the scope of his work has increased, and prints of his maps have become coveted, to employ assistants to help in some of it. He tries to resist that impulse. “I go into art shows and see these vast works that other people have made for the artist,” he says. “With my subject matter, though, it is all about human residues and traces that have often taken a long time to come about and settle in the geography, so I think you have to do that process justice in your own methods somehow.”

Walter, as a child, always loved that leap you have to make from looking at maps to imagining what the landscape they represented was like. He would pore over Tolkien’s Mordor. He starts working on a new map now as he might begin plotting a novel: going through audio archives, reading books, interviewing people – and of course poking around in corners of the city. He has, in the past, done work towards comparable maps of Liverpool and Manchester and Berlin, but it is to London he has returned, partly because it is home, and partly because it understands itself through his kind of accreted historical layering.

As well as elevating the handmade, the maps are a melting pot of all those stories, the theatre of them. “Some stories stick to places,” Walter says. “In the etymology of place names you are probably going back thousands of years, way past written history.” Those places still in Walter’s imagination retain traces of their original meaning – the comforts of Homeystead (Hampstead), the pagan origins of rough and ready Seven Sisters. That is why, he suggests, something like the Olympic park seems so alien. “It is a very broad eraser through what was there before.”

When Walter’s Island was displayed alongside the early hand-drawn maps of London at the memorable British Library show Magnificent Maps: Power, Propaganda and Art of 2010 it became clear that any map is, as he says, “always a projection of the views and opinions of its maker”.

Some of his own projection is quietly comic, the obsessive city dweller’s mind map. But it is, also, an act of reclamation, reminding us that the built space is ours to live within, refusing the A-Z of ownership and statute, and reaffirming the thing that really binds the city: the stories all of its citizens share in their heads.

I wonder at one point if Walter has any interest in ley lines and those who would divine in London a new Jerusalem.

He laughs. “I don’t buy geomancy,” he says. “I am much more interested in Alfred Watkins, who wrote The Old Straight Track in 1925. The ley lines were the most direct routes for getting from A to B to trade or whatever. That history has enough magic for me. I don’t need dowsers to find that past wonderful.”

A lyrical imaginative piece responding to the Faerie Land exhibition, from the blog of Arthurian writer, thinker and esotericist, Gareth Knight (online). The following is an extract, the full piece can be read online.

http://garethknight.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/faery-lore.html

An exhibition on the subject of Faeryland at the Royal Geographical Society (of all places!) from the 10th to the end of September stimulates me to repeat a few lines that I once wrote on the subject.

Faery lore has always been with us, as long indeed as faeries, but only in the last twenty years has it come to such prominence. This largely thanks to R J Stewart who has published some very practical books on the subject, starting with The UnderWorld Initiation in 1985, passing through Earth Light and Power within the Land in 1992, to The Living World of Faery in 1995 and The Well of Light in 2004. These have been particularly stimulating works because they present us with an important challenge.

Older forms of tradition speak not so much of intercommunication as of complete transition. Either a human is lured into faery land – or a faery enters the human world – visitors in an alien environment to that in which they were born. And such adventures tend to end in grief. Either the human being cannot find the way back, or if successful crumbles to dust, having been away for a very long time indeed in a different time dimension. Or the faery is driven back to fairyland because the human being breaks faith in some way, unable to unwilling to fulfil the conditions of such an unusual relationship.

There are of course rare cases where a successful transition seems to have taken place. The most celebrated being the 13th century Thomas the Rymer and his seven year dalliance in the hills with the Faery Queen. Or the successful recovery of Tam Lin from fairyland by a persistent and courageous human lover. All of which demonstrate that we are not dealing with a fluffy bunny kind of world when we approach the faery condition, but nor, on the other hand, are we consorting with demonic agencies as monkish scribes have tended to describe them.

Apart from ballad lore, which R J Stewart, as a musician has explored in some depth, there are other areas in which it is profitable to look, particularly in medieval times when humans and faeries seem to have been more closely connected than they are now. Perhaps because humans tended to believe in them more. On the one hand are the historical traditions of certain families that have claimed faery ancestry, and on the other early versions of Arthurian legend.

Three ancient families in particular spring to mind – those of Bouillon, of Anjou and of Lusignan.

The first concerns King Lothair of Lorraine who allegedly met a faery in the woods who bore him seven children, one of whom became the Knight of the Swan who sailed down the Rhine one day in a boat to champion Beatrice of Bouillon who was having some trouble with a local lord. He married Beatrice’s daughter Ida but left her when (despite his strictures) she became too curious about his origins.

The second was the powerful and widespread family of Anjou. An early member of the family, Fulke the Black, was said to have married a water sprite, who bore him at least two children before disappearing through the roof of the church in great distress when compelled to attend the consecration of the mass (an obvious monkish interpolation). This monkish libel did not faze the family at all in after years. Richard Coeur de Lion in particular revelled in being a member of “the Devil’s Brood!”

A third instance is that of the family of Lusignan, which like the town named after them near Poitiers, was founded by the faery Melusine, who originally hailed from Scotland, and returned to Avalon when after some marital strife her husband publicly called her a demon.

In 1099 a leader of the 1st Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon became the first ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1099, and in 1101 his brother Baldwin its first king. Then thirty years on, when that line had died out, Fulke V of Anjou married the heiress to the kingdom, the princess Melisende, thus establishing the Anjou line on the throne. And by a similar process of marrying an heiress to the kingdom, the crown passed to two Lusignan brothers, first Guy who, had married the princess Sibylla, in 1186 and then Amalric who wed her half sister Isabella in 1198.

There is plenty of room for conjecture here as fascinating as holy bloods and holy grails, which has given me plenty to mull over for some time to come. But there are more significant indicators of a close human faery interconnection to be found in a close reading of Arthurian legend.

Particularly early legend, recorded a couple of hundred years before Sir Thomas Malory set pen to paper in about 1370 to produce Le Morte d’Arthur. Admittedly it is a classic of English literature but in which, despite Morgan le Fay and the Lady of the Lake, much of the faery content is lost. Sir Thomas, a contemporary of Henry V and Agincourt, was more focused on the conventions of feudal chivalry in the human world. To find the faeries coming out of the woodwork we need to go back to around 1170 when Chrétien de Troyes, the court poet of Countess Marie of Champagne, was versifying the first Arthurian romances. Not that Chrétien (who thought himself a very modern 12th century man of the world) entirely believed in faeries, but he was drawing his material from older sources who did.

And when we examine his stories in depth, we realise that the commonplace romantic scenario was not so much human damsels in distress calling upon knights to go and solve their problems. It was more a case of a faery woman acting as initiator of a human knight into the faery world.

This seems to have been the case with regard to Erec and Enide, (Geraint in the Mabinogion version), for although it appears to be Erec who is taking the initiative, it is really Enide who is calling the shots and leading him on into his various adventures, ending up in ruling a dual kingdom with her. Similarly Yvain after certain rites at a magic fountain is led on by Lunette through a series of tests that end up with him married to the faery Laudine. Even in the Grail romance Percival has his Blanchefleur and Gawain his Orgueilleuse of Logres as intermediaries on the way to very faery locations – one the Graal castle and the other the Castle of Maidens. And Lancelot’s adventures to rescue Guenevere plainly take place in a faery kingdom. All this I have spelled out in some detail in The Faery Gates of Avalon, in the hope that it will encourage others to go back to the tales, keeping an eye out for the faery dynamics, which become obvious once one knows what to look for.

This also applies to slightly later versions of Arthurian Legend such as the Lancelot Grail of 1220/30. Wendy Berg has shown in her remarkable work, Red Tree, White Tree – Humans and Faeries in Partnership, (Skylight Press 2011), that this stratum of legend leads to the conclusion that Queen Guenevere herself was one of the faery kind.

This view of Guenevere is no new agey fad, for the possibility has been seriously put forward by academics of some distinction, in Guinevere, A Study of her Abductions by Professor K G T Webster in 1951, and Lancelot and Guenevere by Professors T P Cross and W A Nitze in 1930. It is simply that Wendy, with her keen esoteric sense, has brilliantly illuminated a neglected academic thesis, and shown the whole Arthurian scenario in a new light. The light of Faery.

Guenevere was abducted on a number of occasions, but rather than passing her off as some kind of Persephone figure connected to the cycles of nature, a role which she really does not fit, a more likely possibility could have been the faery world trying to get her back! We find much the same kind of situation in Fiona Macleod’s The Immortal Hour where the faery Etain is taken back to fairyland after having wandered into the human world and been married to the Eochaid, the High King of Ireland.

Following this theory through leads to some startling conclusions as to the origin and destiny of the Grail Hallows, which as sword and lance and cup and stone, came originally from faery land. And which – like Arthur’s sword Excalibur – need to be returned there. Hence the need for the legend of Joseph of Arimathea returning the Graal to Logres, from whence it had been taken to Sarras (the inner side of Jerusalem) by the Grail heroes in the Ship of Solomon. Whilst the two cruets associated with his mission back to Glastonbury, one containing a red liquid and the other a white, signify amongst other things, the sap of the red tree and the white tree, the human and faery blood lines.

This provides the prospect for some exciting esoteric work. As Wendy points out, if it was the duty and opportunity of the knights (of whom we are the modern equivalent) to seek out the structure and nature of Faery, one way of doing this today may be to give more attention to way showers such as Melusine, Etain and Gwenevere. Those who left behind their birthright in the Immortal Clan to enter the human world. And there the challenge rests. Are we capable of responding to “the faint call of Faery” and taking steps to answer it?