Michael Drayton was born in 1563 in the sleepy hamlet of Hartshill in north Warwickshire, three miles south of the market town of Atherstone. His origins were humble: his father and grandfather, both named William, were yeoman, working as tanners or butchers. Other relatives were farmers and shoemakers. Nothing is currently known about his mother but her name, Katherine.

The woodlands, brooks and meadows of his rural Midlands boyhood were to become constants within his poetic imagination: like his fellow shireman, Shakespeare, his “native wood-notes wild” form an ever-present background refrain, even in his more courtly confections.

While he made his home and forged his career in London, he nevertheless remained firmly rooted in the Warwickshire greenwood, despising the city’s excesses and fripperies, writing in Song 19 of Poly-Olbion:

Fooles gaze at painted Courts, to th’ countrey let me goe, To climbe the easie hill, then walke, the valley lowe; No gold-embossed Roofes, to me are like the woods, No Bed like to the grasse, nor liquor like the floods: A Citie’s but a sinke, gay houses gawdy graves…

The River Anker, which flows in the valley below Hartshill, attracts the most encomiums in Drayton’s writing, however, due to its association with his muse Anne Goodere (1570-?), whose family home, Polesworth, lay further down its course in the middle of the Forest of Arden. While literary historians are divided as to the exact nature of their relationship, Anne nevertheless haunts his work. He calls her his ‘deerest Love’ and she became the beautiful, virtuous, and indifferent mistress ‘Idea’ of Ideas Mirrour. Amours in Quatozains (1594). The unpublished verses he penned to her memory ‘the night before he dyed’ at Christmastide 1631, preserved in the Bodleian Library (MS Ashmole 38, fol. 77), remain some of the most moving and raw in English literature.

The Goodere family were vital to Drayton’s ambitions as a writer and his life became entwined with theirs to the third generation “by bonds of loyal service, tenderest affection and devoted and enduring friendship.” According to the information provided by Drayton himself in his elegy Epistle to Henry Reynolds, in 1573, at the age of ten, Drayton seems to have entered the service of Anne’s father, Sir Henry Goodere as “a proper goodly page.”

He shared tutors with the Goodere children and at some point attended a grammar school, possibly at Coventry, where Henry had a second home. His yearning to become a poet began early (“from my cradle…I was still inclin’d to noble Poesie”) and he writes, how “scarse ten yeares of age,” he hugged his “milde tutor” begging to be made into a poet (again from Epistle to Henry Reynolds, 1627):

O my deare master! cannot you (quoth I)

Make me a Poet, doe it; if you can.

To the amusement of C.S. Lewis, writing of the incident in his English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, the tutor granted his request in typically Elizabethan fashion, by starting him off on Mantuan’s eclogues (the Italian humanist’s absurdly popular pastoral collection was always being handed out to schoolboys in the seventeenth century: Shakespeare calls him “good old Mantuan” in Love’s Labour’s Lost). Interestingly, according to Bernard H. Newdigate, whose passionate and groundbreaking wartime biography of Drayton remains the standard reference, this obliging tutor could have been the internationally acclaimed scholar Leonard Cox, a friend of Erasmus and Sir Thomas More, who supposedly taught at Coventry as a very old gentleman in the 1570s. If so, it would link Drayton’s formative education directly with the European school of humanist discourse.

In any case, he evidently had sturdy teaching of some kind, writing in 1597 to the son of Sir Henry that he owed the better part of his education to the Gooderes’ “happy and generous family,” and his reading was both “wide and deep.” Apart from his contemporaries, we find clear evidence in his poems that he read the standard classical authors and among the earlier English poets he draws on the works of Chaucer, Langland and Skelton, amongst others. In the mediaeval legend corpus of Arthur, Bevis of Hampton, Robin Hood and Guy of Warwick, he found food both for his poetry and for his ache for a long-lost English golden age.

But as Newdigate emphasizes, while this was all grist for the poetic mill, it was his intense reading of the old English chronicles that would have the most influence upon his work, particularly Poly-Olbion. Far from taking his history at second hand from popular antiquarians John Stow or William Camden, he went directly to the original sources: including Gildas, Bede, Giraldus Cambrensis, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Hoveden, Higden, Nicholas Upton, Philip de Commines. Later, for precise chorographical details for Poly-Olbion, he consulted rare manuscripts, some belonging to Camden, with whom he was friends.

From 1575 to 1585, he was in the service of Thomas Goodere, Sir Henry’s brother, and then returned to Polesworth. Possibly after a spell in the army in the Low Countries, resolute in his ambition to dedicate his life to poetry, by 1590 Drayton was firmly settled in London, “looking for laurels and patrons,” as historian Anne Lake Prescott sharply remarks. He may have been supported by the Russell or Sidney family for a while, although scanty evidence exists for the period spanning from 1591 to 1595.

His career as a published writer began quietly in 1591 with The Harmonie of the Church, a versification of various biblical passages, which Lewis describes as “drab scriptural paraphrases to which critics are too kind when they accuse them of wooden reality, for they are in reality wooden without being regular.” In 1594, however, he began to come into his own particular form of pastoralism with his Idea: the Shepheards Garland, nine eclogues dedicated to young Robert Dudley and modelled on Spenser’s Shepheardes Calender. In 1593, Drayton also published the first of his historical poems: Peirs Gaveston, Earle of Cornwall.

- Tim Yau, Portrait of Anne Goodere, Drayton’s muse

In 1594, the sequence of fifty-one sonnets entitled Ideas Mirrour: Amours in Quatorzains was printed at the height of the vogue for the form. Its dedication to Anthony Cooke proclaimed that his “rude unpolished rhymes” had “long slept in sable night,” and it is evident that they were written at intervals some years before they were printed. For the romantic Newdigate, these “early Sonnets have Anne Goodere, Drayton’s Idea, alone for their subject and…were hammered out in the white heat of a love pure and passionate:”

My hart the Anvile where my thoughts doe beate, My words the hammers, fashioning my desires, My breast the forge, including all the heate, Love is the fuell which maintaines the fire.

In 1595, Drayton published Endimion and Phoebe, dedicated to the fourteen-year-old Lucy Harington, now Countess of Bedford, whose later sudden withdrawal as a patroness would cause him such bitterness and biliousness that it seeped dangerously into his poetry, with thinly-disguised attacks on her infidelity and treacherousness.

The following year, Mortimeriados was dedicated to her, but in 1603 the disappointed poet withdrew the dedication and cancelled various other flattering references. Set in the civil wars during the reign of Edward II, Mortimeriados is a gory, blood-splattered quasi-epic that he was never particularly happy with. It was finally republished in 1603, packed with informative marginalia, as The Barrons Wars. Englands Heroicall Epistles was first issued in 1597 and was to be among the most popular of Drayton’s works: reprinted numerous times and a source of much needed revenue for the poet. Modelled on Ovid’s Heroides, at least in terms of genre but with more focus on history than remote legend, it comprises paired epistles between famous lovers, such as Henry II and Rosamund, Edward IV and Mistress Shore and Queen Margaret of Anjou and William de-la-Poole.

- Lucy, Countess of Bedford, National Portrait Gallery

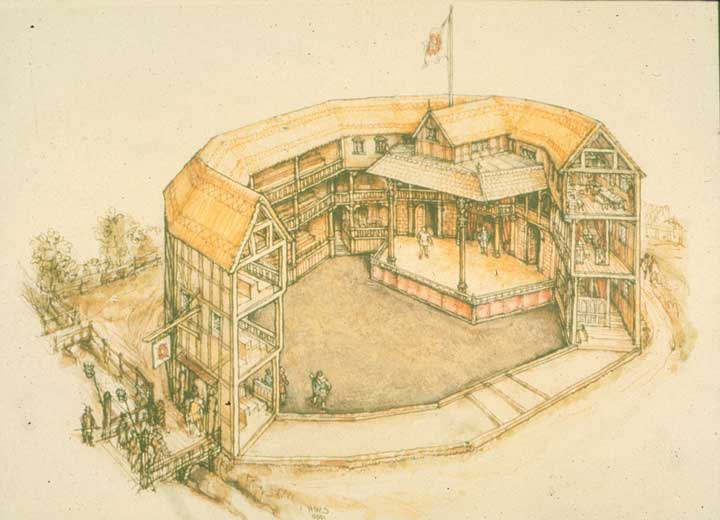

After his great falling out with the Countess of Bedford, it is thought that Drayton must have found himself with severe financial problems, as he suddenly began to produce hackwork for the theatre trade. He became a sweat-shop playwright, churning out play after play with various teams of writers, including Anthony Munday, Thomas Dekker, Henry Chettle, John Webster and Thomas Middleton.

From late 1597 to 1604 he wrote more than twenty plays for the impresario Philip Henslowe and the Lord Admiral’s Men. 1598 alone saw about a dozen, although some were perhaps never completed. The First Part of Sir John Oldcastle, written with Robert Wilson, Richard Hathway, and Munday (printed in 1600) and later sometimes included with Shakespeare’s works, is the only one of these to survive. The titles of the lost works, preserved in Henslowe’s diary are intriguing (including The Funeral of Richard Coeur-de-Lion; Hannibal and Hermes; Mother Redcap and The Madman’s Morris) and one wonders how Drayton’s reputation may have been preserved had they not been lost. Unfortunately, he omitted his plays from his collected works (1619) and seems to have found the whole experience of writing for the theatre profoundly frustrating. At this time, he also had temporarily to abandon his Poly-Olbion, which he had already begun to compose.

- Cross-section of the Rose Theatre, 1592

In 1603, Elizabeth I died: an event which profoundly shook the nation. Like many other poets, Drayton looked at her death as a possibility for new royal patronage, for he quickly published To the Majestie of King James: a Gratulatorie Poem and the following year saw A paean triumphall: composed for the societie of the goldsmiths of London, congratulating his highnes magnificent entring the Citie. All in vain, for James completely ignored Drayton and his flattery. Henry Chettle’s Englandes Mourning Garment (1603) suggests that Drayton had been tasteless in so speedily courting his new monarch:

Thinke twas a fault to have thy Verses seene

Praising the King, ere they had mournd the Queen.

From this point onwards, his feathers extremely ruffled, Drayton was unsurprisingly rather bitter towards James I in his poetic works. His courageous political satire The Owle (1604) was, as Hardin writes in Michael Drayton and the Passing of Elizabethan England (1973), “received as a roman à clef, by which news-hungry Englishmen might read gossip about the great, couched in obscure language.” Unfortunately, the meaning is so well-hidden within that obscure language that the full satiric intention of the poem is almost incomprehensible today.

Following the tradition of Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules, it is structured around a gathering of birds mirroring human types and highlighting the evils abroad in the kingdom, particularly at Court. Most of the characters are now lost or obscured to us, however, apart from an arrogant oak who recalls the rebellious and ill-fated earl of Essex, who had been executed for treason in 1601. Drayton dedicated The Owle and his 1605 collected Poems to the wealthy and appreciative Sir Walter Aston, who became a supportive patron for many years. At his investiture as knight of the Bath in 1603, Aston had made Drayton one of his esquires, a title that was a source of great pride to the humbly-born poet and, as such, is prominently displayed on all of his subsequent title pages.

In 1606, Poemes Lyrick and Pastorall: Odes, Eglogs, the Man in the Moone was published. It contains some of Drayton’s most influential and luminous poems, including the oft-quoted Ballad of Agincourt (“Fair stood the wind for France”), with its implicit criticism of the pacifistic James and the ode To the Virginian Voyage, inspired by Hakluyt’s Voyages and full of colonizing fervour, describing the settlement at Virginia as an earthly paradise mirroring England’s past golden age. Other editions followed, that of 1610 with a commendatory sonnet by the antiquary and scholar John Selden, who was later to provide historical commentary to Poly-Olbion.

The eerie Legend of Great Cromwel, in which Thomas Cromwell’s ghost tells the story of his own rise and fall, elaborating on the medieval theme of the rota fortunae, was published in 1607: one of the first critical accounts of Henry VIII’s reign. Again, contemporary political criticism is tightly woven into its narrative.

Then, in 1612, he published the first eighteen songs of Poly-Olbion, his defining poetic project. He had been working on this magnum opus at least since 1598. The impressive volume included a portrait of Prince Henry, the poem’s dedicatee, whose admiration for Drayton, if only as a means further to distinguish himself from his father, shows in the £10 annuity listed in his privy purse accounts. Even with a royal patron, Drayton had trouble finding a publisher for the work.

In a letter dated 14 April 1619, he wrote to “dear, sweet (William) Drummond,” with whom he maintained a lively correspondence, thanking him for his “good opinion of Poly-Olbion.” The new part, Drayton says, “lyeth by me; for the Booksellers and I are in Terms: They are a Company of base Knaves, whom I both scorn and kick at.”

Eventually, in 1622, he published all thirty sections, although without additional annotations by Selden. See here for further information about the poem and its role as the project’s inspiration.

In 1619, Poems by Michael Drayton Esquyer, dedicated again to Aston, containing heavily rewritten versions of all poetry except Poly-Olbion. A volume of miscellaneous works, The Battaile of Agincourt, appeared in 1627, which, according to Prescott may have been hurried into print as “background marching music” for the duke of Buckingham’s imminent campaign in France.

- Sir Walter Aston, Drayton’s patron (Burton Constable Hall)

The collection’s best-known poem is Nimphidia, the Courte of Fayrie, whose diminutive world of fluttering sprites has been as influential as Midsummer Night’s Dream in shaping visions of the faerie world. The sylphs of Pope’s The Rape of the Lock, for example, are directly influenced by Drayton, for example. The volume is prefaced by verses from friends and admirers, not least Ben Jonson.

Dedicated to the earl of Dorset, Drayton’s last book was the exquisite The Muses Elizium, lately discovered, by a new way over Parnassus…Noah’s floud, Moses, his birth and miracles, David and Golia (1630). In the main body of the volume, ten “nimphalls” describe a “Poets Paradice”, a place of “continuall summer” and perfect beauty, in which down-trodden and world-weary poets can wander far from the corruptions of modern life and where “blessed bowers” are “free from the rude resort of beastly people.” This space is more remote and inaccessible than the transformative and joyous green worlds of Shakespeare’s forest comedies: it is completely self-contained and otherworldly. And indeed, Lewis writes of the first “nimphall” that “it is thus that real fairies would speak if they existed.”

That longing for an otherworldly haven was heartfelt by Drayton, who was an outsider in his own times, always marching slightly out of step with his contemporaries. Poly-Olbion took him so long to write that literary fashions had entirely changed by the time it reached publication and his exuberant vision of a united Britain never received the admiration and attention for which he had so desperately longed: Drayton writing that

I have met with barbarous Ignorance, and base Detraction; such a cloud hath the Devill drawne over the Worlds Judgement, whose opinion is in few yeares fallen so farre below all Ballatry, that the Lethargy is incurable.

Even his first collection of sonnets, Ideas Mirrour, published when sonneteers were at their most popular, have a completely novel feel to them: “a strange wild beauty …almost as if Marlowe were writing sonnets,” says Hebel.

In the anonymous play, Return from Parnassus (1605), Judicio proclaims that while Drayton’s

sweet muse is like a sanguine dye,

Able to ravish the rash gazers eye

he lacked “one true note of a Poet of our times, and that is this, hee cannot swagger it well in a Taverne, nor dominere in a hothouse.” Unlike Marlowe, Jonson or Donne, Drayton seems to have been too “virtuous”, too “honest” (according to Francis Meres), self-doubting and mild-mannered to command the literary scene: he just wasn’t sexy or confident enough, he didn’t swagger it enough to carry fashion with him, regardless of how original his work was.

Yet he enjoyed a supportive and stimulating circle of distinguished friends and admirers, including fellow poets and dramatists such as Richard Barnfield, Thomas Lodge, Joshua Sylvester, Sir William Alexander, Francis Beaumont, William Browne and William Drummond of Hawthornden. In the close-knit London theatre world, he would have known Shakespeare, although no written evidence for a friendship remains except a note made around 1662 by John Ward, vicar of Stratford upon Avon, that mentions a “merry meeting” at which Shakespeare, Drayton, and Jonson “dranke too hard, for Shakespear died of a feaver there contracted.” And, in terms of patronage, even if disappointed by the Countess of Bedford and James, he had strong support from Sir Walter Aston, Anne Goodere (who became Lady Rainsford) and Sir Edward Sackville, Fourth earl of Dorset, amongst others.

Despite his problems with patrons, publishers, kings and apathetic critics, Drayton was nevertheless much read and published in his own day. While the eighteenth century saw a cooling of interest, Romantic and Pre-Raphaelite writers and painters seized upon his work in the nineteenth. Wordsworth threads ideas and images from Draytonian worlds through his own eco-poetic landscapes, much of William Blake’s mystical iconography and nomenclature is derived from Drayton’s chorography and towards the end of the century, Thomas Hardy includes a number of Poly-Olbion allusions in Jude the Obscure to deepen the sense of archaism and meaning within his evocation of places such as Shaftesbury.

It is Drayton’s sensitivity to the fragility of the natural environment and his unease at the erosion of England’s beauty that his “monstrous Age” was enabling, particularly in relation to her forests and woodlands, that represents a particularly strong undertow for these and other writers. As Andrew McRae has pointed out, Poly-Olbion offers one of the most important and critically neglected early modern discourses on environmentalism. In his novel Howards End (1910), E.M. Forster devotes a whole passage to Poly-Olbion, imagining Drayton’s progress across a industrialised England in a car, rather than over the Elizabethan greenwood via his original airborne poetic muse:

A motor-drive, a form of felicity detested by Margaret, awaited her….But it was not an impressive drive. Perhaps the weather was to blame, being gray and banked high with weary clouds. Perhaps Hertfordshire is scarcely intended for motorists. Did not a gentleman once motor so quickly through Westmorland that he missed it? And if Westmorland can be missed it will fare with a country whose delicate structure particularly needs the attentive eye. Hertfordshire is England at its quietest, with little emphasis of river and hill; it is England meditative. If Drayton were with us again to write a new edition of his incomparable poem, he would sing the nymphs of Hertfordshire as indeterminate of feature, with hair obfuscated by the London smoke. Their eyes would be sad, and averted from their fate towards the northern flats, their leader not Isis or Sabrina, but the slowly flowing Lea. No glory of raiment would be theirs, no urgency of dance; but they would be real nymphs.

This love for England and horror at the loss of her heritage and pre-industrial landscape is exemplified by Harold Hannyngton Child’s words in the Times Literary Supplement of December 1931:

At the present moment the great work (Poly-Olbion) is more apt to be in favour than ever before, just because the changes in England are so swift and so many as to sharpen our antiquarian interest and to set us looking back to almost any ancient account of the places we know and love. And, therefore, we take a pious delight, as it were, in getting out of our swift and new motor-cars.

Newly relevant, the twentieth century saw a rapid increase in Draytonian scholarship and publications, notably the Shakespeare Head Press five-volume set of his complete works begun by the American academic William Hebel and completed by Kathleen Tillotson (1931-41) and Newdigate’s wartime contextual study of friends and patrons (1941). Despite these landmark texts and the increasing trickle of new analysis, from the multiple perspectives of New Criticism, New Historicism, landscape and cartography studies, Drayton is still unknown outside of academia and relatively neglected within. This general disregardance needs to be addressed: Drayton’s contribution is too important to fundamental elements of our national discourse to languish in second-tier anonymity.

- H.E. Bates’ Fair Stood the Wind for France took its title from Drayton’s Ballad of Agincourt

But Drayton is not only relevant to the collective, but also, as his admirers have affirmed throughout the centuries, to the individual in search of hearty poetic sustenance. As Prescott eloquently puts it:

Drayton can move from abstract Neoplatonic flights to pastoral retreats free of royal neglect and the sad need to scramble for funds; to grieved witness of Time’s hungry destruction of women and walls; to ironic visions of court life; and to an image of the British landscape in which rivers with excellent historical memories, boastful hills that look down on equally voluble valleys, rivers that run on at the mouth, self-assured towns, and lively fauna leave scant room for monarchy as the Stuarts conceived it. Drayton…repays the reader, especially one looking less for the stolid moralism or simple patriotism with which he has been too often identified than for sardonic melancholy, political resistance, airy delicacy, and access to realms invisible to the merely well born or rich. Any poet who can, in the poem Robert, Duke of Normandie, have Fortune tell Memory, with a savage pun, that “Written with Bloud, thy sad Memorials lye” deserves attention.

Drayton died in London on 23 December 1631, in his lodgings in Fleet Street next to St Dunstan’s Church He left an estate of £24 2s. 8d. According to the antiquary William Fulman, Drayton’s death was marked by considerable public ceremony and mourning: “he dyed at his lodging in Fleet Street below Saint Dunstans Church, not rich; but so well beloved, that the Gentlemen of the Four Innes of Court and others of note about the Town, attended his body to Westminster, reaching in order by two and two, from his Lodging almost to Strandbridge (near present Catherine Street).”

- Poet Paul Farley reading at our memorial servicce for Drayton at Westminster Abbey

Extract from The Faerie Land: Michael Drayton’s Vision of Britain (exhibition catalogue, FOS Publications, 2015)

Anne Louise Avery, Director, Flash of Splendour.